Commercial aviation is the cornerstone of our economy and society. It enables the rapid movement of goods and people around the world, facilitating more than one-third of global trade in terms of value and supporting 87.7 million jobs worldwide.

But even an 80-ton flying machine flying at near-supersonic speeds comes with its own set of environmental challenges. Simply changing flight routes could dramatically reduce climate impacts.

Modern aircraft burn kerosene to create the thrust needed to overcome drag and create lift. Kerosene is an energy-dense fossil fuel, providing a lot of energy per kilogram burned. However, combustion primarily releases harmful chemicals such as carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), water vapor, and particulate matter (soot, dirt, and small particles of liquid).

The aviation industry is widely known for its carbon footprint, with the industry contributing 2.5% of the world’s CO2 pollution.

Some might argue that this pales in comparison to other sectors, but carbon accounts for only one-third of the total climate impact of aviation.

Non-CO2 emissions (mainly NOx and ice trails from aircraft water vapor) account for the remaining two-thirds.

When all aircraft emissions are taken into account, flying is responsible for about 5% of human-induced climate change. Given that 89% of the population has never flown, passenger demand is doubling every two decades, and other sectors are decarbonizing at a faster rate, these numbers are expected to skyrocket.

Not just carbon, the aircraft spends most of its time at cruising altitudes (33,000 to 42,000 feet), where the air is thin enough to minimize air resistance.

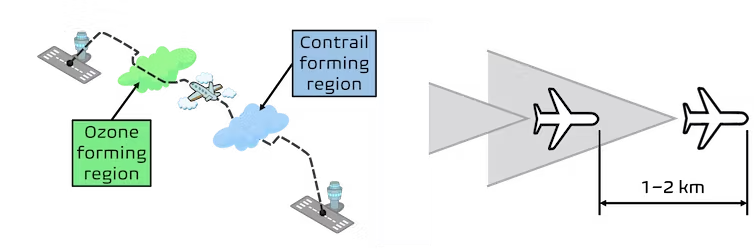

At these altitudes, aircraft NOx reacts with atmospheric chemicals to produce ozone and destroy methane, two very potent greenhouse gases.

This aviation-related ozone should not be confused with the natural ozone layer, which is much higher and protects the earth from harmful UV rays. Unfortunately, NOx emissions from aircraft cause more warming through ozone production than cooling through methane depletion.

This translates into a net warming effect that accounts for 16% of the total climate impact of aviation. Even if the air temperature is below -0°C and the air is moist, the water vapor in the aircraft will condense into particles in the exhaust and freeze.

This creates a cloud of ice called a contrail. Contrails may be made of ice, but they warm the climate by trapping heat emitted from the Earth’s surface.

Contrails last only a few hours, but they are responsible for 51% of global warming in the aviation industry. In other words, we are warming the planet more than the CO2 emissions from aircraft have accumulated since the dawn of powered flight. Unlike carbon, non-CO2 emissions cause heating through interaction with the surrounding air. Their climatic impact varies with atmospheric conditions at the time and location of the release.

Two of the most promising short-term options for mitigating climate impacts without CO2 are climate-optimized routing and formation flying.

For climate-optimal routing, aircraft are diverted to avoid areas of the atmosphere that are particularly climate-sensitive. For example, particularly moist air causes long-lasting, harmful contrails to form. Studies have shown that even a modest increase in flying distance (typically less than 1% of travel) can reduce the net climate impact of flying by about 20%.

The flight operator can also reduce the impact of aircraft by flying in formation, with one aircraft flying 1-2 km behind the other aircraft. The trailing aircraft “surfs” the trail of the leading aircraft, reducing CO2 and other harmful emissions by 5%.

But flying in formation can also reduce global warming in addition to CO2. Overlapping aircraft plumes accumulate the emissions they contain. When NOx reaches a certain concentration, the rate of ozone production slows down, reducing the warming effect.

When contrails form, they grow by absorbing the surrounding water vapor. During formation flight, aircraft contrails compete for water vapor and become smaller as a result. Combining all three reductions, formation flying could reduce its climate impact by up to 2%.

Decarbonization of aviation will take time

The aviation industry has focused on addressing carbon emissions. However, the industry’s current plans to reach net zero by 2050 imply an ambitious 3,000-to 5,000-fold increase in sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) production, troubled carbon offset programs, hydrogen and electric Based on the introduction of aircraft,

It could take decades for all of this to make a difference, so it’s important that the industry reduces its environmental footprint in the meantime.

However, climate-optimized routing and formation flying are purely carbon-centric and are two important examples of how change can be affected more quickly compared to the approach. However, there are currently no political or financial incentives to change course. It’s time for governments and the aviation industry to listen to the science and take non-CO2 emissions from aircraft seriously.

Source-The conversation