New mobility services—everything from bicycle and electric scooter rentals to car sharing and smart parking systems—are growing rapidly and can reduce congestion, pollution, and reliance on private cars.

That’s a big win for city governments that offer bike lanes and other adoption incentives.

However, implementing these services effectively while maintaining essential public transport networks requires careful planning and this does not always happen. Lifestyle changes due to the pandemic have made the task more difficult, accelerating the adoption of new services in some cities, in some cases very quickly.

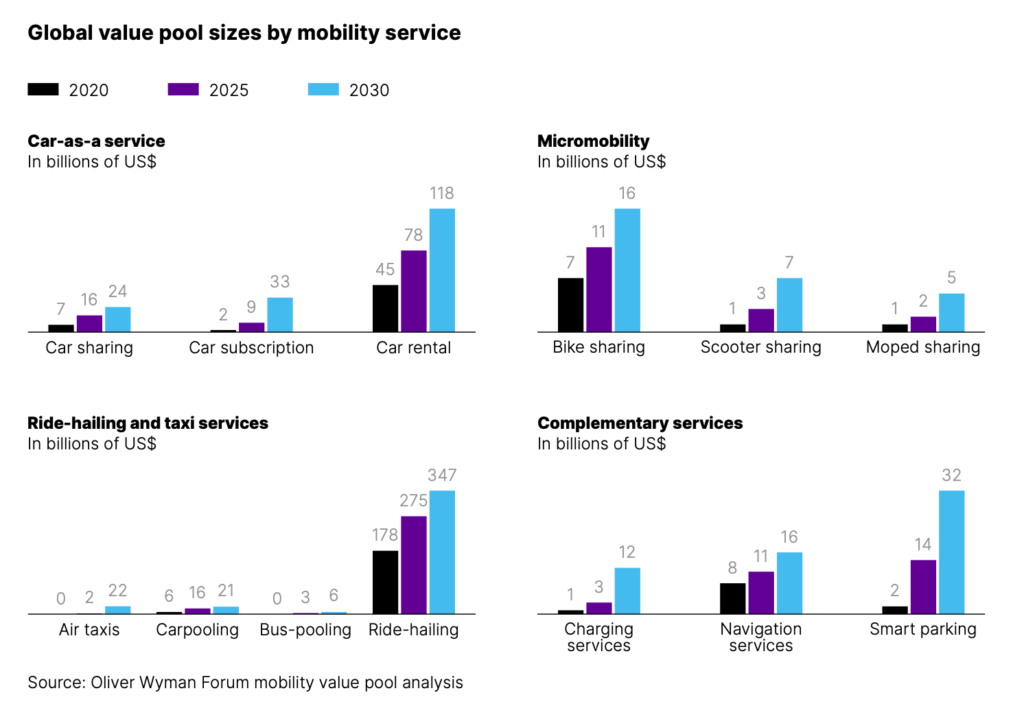

Global annual revenue for the 13 most popular new services is expected to grow to $660 billion in 2030, up from $260 billion in 2020, according to a recent study by the Oliver Wyman Forum and the University of California Transportation Research Institute, Berkeley.

Such growth was not a problem at the peak of the pandemic, as public transport was largely closed or restricted. But the race between new and old mobility is becoming a major challenge now that efforts to get workers back into the office are accelerating and streets and trains remain clogged.

In the long term, cities can encourage new forms of mobility without reducing public transport trips in three main ways.

1. Utilizing micromobility

Cities can take full advantage of micromobility services that allow users to rent electric scooters, bicycles, and mopeds for individual trips by initially focusing on areas with limited or no public transport. While electrified buses, streetcars, and light rail systems are arguably the most efficient and environmentally friendly forms of motorized urban transport, they don’t get people everywhere they want to go.

Micromobility can provide the last leg of commuter travel, especially in cities with fewer train stations.

An average electric scooter trip takes only about 12 minutes. Even in the car-dominated United States, 60% of all trips are 8 km or less, distances that can easily be covered by e-bike or moped. Micro mobility can sometimes provide a cheap and low-polluting alternative to taxis. Subsidies for poor commuters to use micro-mobility services can also promote social equity.

To increase the synergy of new mobility and public transport, cities can set up micro-mobility centers in metro stations. According to a study conducted in Washington, a 10% increase in annual use of the Capital Bikeshare program would increase average daily subway ridership by 2.8 percent. As part of its Mobility Strategy 2035, Munich plans to install up to 200 mobility centers where users can find shared bicycles, cars, and scooters, many of which are connected to metro stations.

The use of micromobility also tends to flourish where there is a separate space for riding, such as bike lanes that run along city streets. After London built two cycle highways, 200% more bicycles passed through one point and 12% more at the other.

2. Use automobiles effectively.

Geographically large and less dense cities are likely to remain car-dependent for the foreseeable future, but car-based mobility services such as ride-sharing, carpooling, and ride-sharing, and on-demand buses can help reduce parking pressure.

A typical private car is parked 95% of the time, and many of these cars prevent road space from being used for other purposes, such as bicycle or tram lines, or lead to the diversion of major urban areas into parking lots. However, driving can increase congestion as many cars drive around looking for customers. Information and sharing services cause emissions if they are not electric. Parking spaces can be better utilized with smart payment systems—online platforms and applications that connect drivers with available spaces and allow them to pay—reducing traffic caused by cars looking for a parking space. Intelligent parking systems have gained momentum in Europe and North America, where the Oliver Wyman Forum predicts huge growth, from $700 million in 2020 to $21 billion in 2030. In the future, new technology will be developed based on satellites or sensors built into the system. which can detect which parking spaces are available and transmit this information to cloud-based platforms, further accelerating autonomous services.

3.Make long-term plans and stick to them

To be effective, measures aimed at promoting new forms of mobility must be part of a wider plan. Cities like Paris are already implementing these strategies. The French capital announced in 2020 that it would become a “city of 15 minutes”, a city where residents can easily reach essential services by bike or foot in that time. Amsterdam, which regularly receives high marks for urban transport, announced in 2019 that it would eliminate 11,000 parking spaces by 2025 to make the city greener and more accessible. It combined this with other strategies, such as people trading in their cars for a shared moving budget for a month or two.

But the policy of implementing these plans is often complex. Some drivers are happy with the reduction in parking spaces. Brussels, for example, is struggling to expand its bike lane network amid complaints about the loss of cheap street parking. Some Parisian businessmen said plans to build 110 miles (180 kilometers) of permanently separated bike lanes between 2021 and 2026 could ruin their business.

That is why it is important to design new policies positively, not against cars. Each measure must clearly improve affordability, the urban environment, and travel from A to B. Finally, cities need a long-term strategy with clear goals that are independent of election cycles, that is too short to significantly improve infrastructure, and that delivers results.

Source:Wef