The World Economic Forum (WEF) met in Davos, Switzerland, last week under the shadow of war and disruption to global supply chains.

The war in Ukraine has taken center stage at the WEF, overshadowing economic growth and business issues that have dominated past conferences.

Growth predictions vary widely by region:

- China’s GDP is growing with an increase of 7% this year; India’s by 6%; Russia’s by 0%; Brazil’s by -3%;

- However, these forecasts are still significantly better than those made just before COVID began last year when the consensus forecast was for 2% growth worldwide.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 20220, published on January 21, said that “rising inflation has been ranked as the most important risk this year.”

The top five risks are:

- Rising prices or cost of living (global average score of 4.30 out of 5)

- Failure of national governance (4.24)

- Natural catastrophes (4.18)

- Failure of climate change mitigation & adaptation (4.16)

- Major epidemics (4.14)

Last year’s optimism of pre-COVID and pre-war conferences has given way to stabilizing the business and the international order in the short term. Indeed, short-term economic growth forecasts have been revised downwardly, but not as much as the popular sentiment would suggest.

The impact on trade and energy prices is also having an effect. The business disruption has led to higher prices for certain products, especially those reliant on oil imports from Russia or transit through Ukraine.

In addition to these direct costs, indirect costs are associated with lower productivity as workers face disruptions to their supply chains because of border closures and roadblocks.

Beyond these direct economic costs, there is also evidence that consumers are less likely to spend money on nonessential goods such as luxury items or entertainment.

This trend will continue into 2022, as well as other geopolitical events unfold worldwide (including Brexit and US elections). According to a new report, the number of people globally who can be considered middle class has fallen by nearly 10 percent since 2021.

World Data Lab (WDL) reported that the number of people living on less than $2 per day fell by almost a third over the same period.

“The definition used by most governments is based on an absolute threshold — whether you earn enough money to buy certain goods like food or clothing — but this approach doesn’t take into account other factors like access to health care and education.”

The report measured poverty based on income and consumption levels, finding that while many countries saw an increase in overall wealth, their populations nonetheless experienced increased levels of relative poverty because they could not keep up with technological advances. What we may see is a recession in some vulnerable countries. To begin with, they haven’t recovered from the COVID-induced crisis. They are highly dependent on energy or food imports from Russia and already have a somewhat weaker environment. But we have not seen that yet.”

The commodity shock has been going on for a while. I mean, when you look at the food price index, it’s been going up for six months. And that’s not just because we’ve had bad weather in some areas. It’s also because of this sense that more people want to eat than ever. Inflation predictions remain elevated for longer than the previous forecast, driven by war-induced commodity price increases and broadening price pressures. By 2022, the inflation rate might hit 5.7 percent in advanced economies and 8.7 percent in emerging and developing economies—1.8 and 2.8 percentage points higher than projected in January.

Conditions could significantly deteriorate. Worsening supply-demand imbalances—including those stemming from the war—and further increases in commodity prices could lead to persistently high inflation.

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) World Economic Outlook Update, released at the end of April, updated its projections for global economic growth and inflation. The outlook remains positive, but it has been revised downward in response to rising trade tensions, growing geopolitical risks, and a more challenging macroeconomic environment.

The IMF’s baseline forecast projects that real GDP will grow by 3.4 per cent in 2019 and 2020; this is 0.2 and 0.1 percentage points lower than projected in January. For 2021 and 2022, world GDP growth is expected to slow to 3 per cent and 2.9 per cent.

Although a gradual resolution of supply-demand imbalances and a modest pickup in labour supply are expected in the baseline, easing price inflation eventually, uncertainty again surrounds the forecast.

The global population has doubled since 1960 and is to increase by another 50% by 2050, which means more people are earning more money and living better lives than ever before. The world has never been so rich and populous — but it has also never been so unequal.

Wealthy countries like the United States are ageing rapidly; many developing countries are growing faster than ever, and this wave of human progress is leaving behind some countries. And while there’s no doubt that we should celebrate our successes, it’s also important to remember that we have much more work to do if we want everyone on Earth to enjoy a happy life with the opportunity for all.

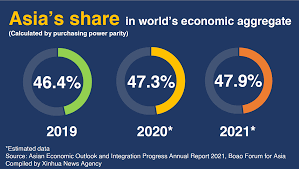

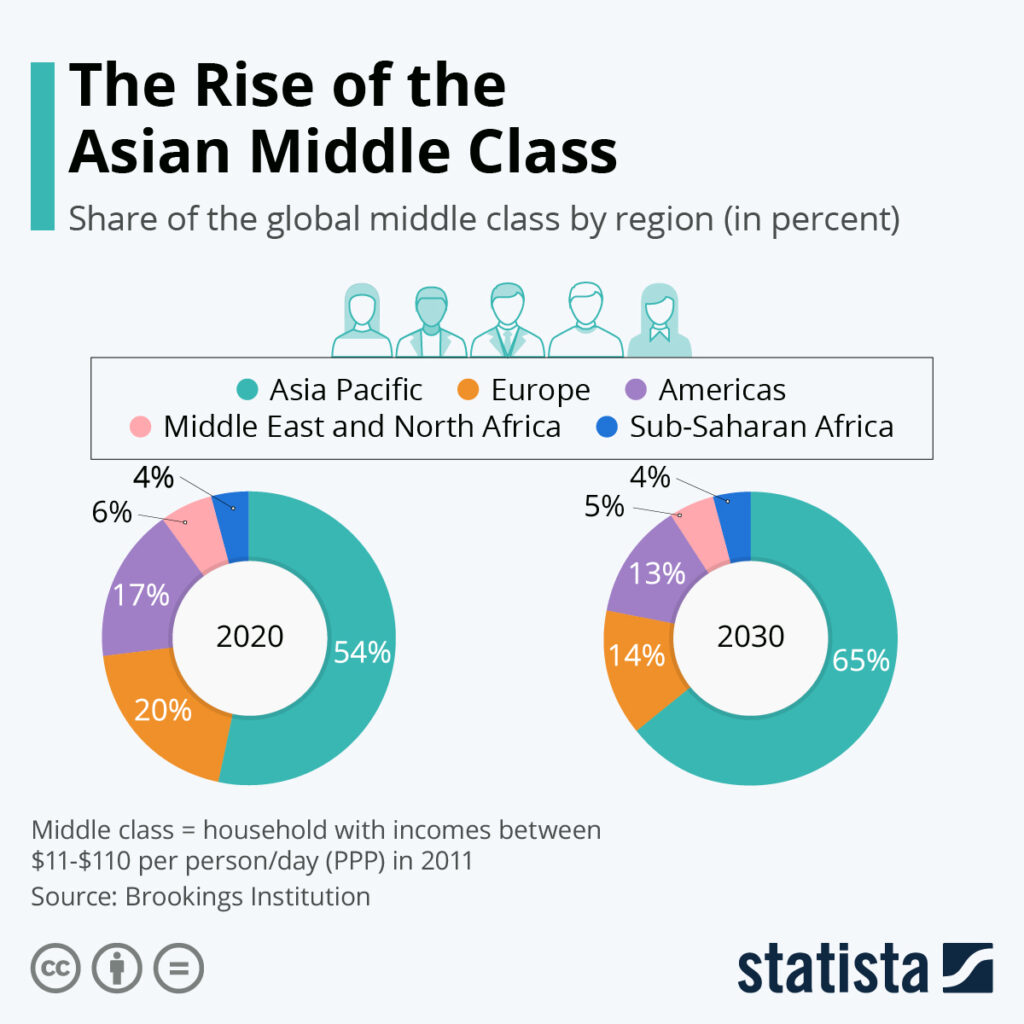

The Asian middle class is growing faster than any other region. It is expected to account for more than half of global consumption growth by 2024.

This demographic shift has already led to a rapid increase in consumer spending and economic growth across Asia — but it’s not just about China anymore.

As Asia continues to grow, so too do its ambitions and interests. Many countries invest heavily in infrastructure and developing their economies beyond their borders — including in Africa and Latin America.

In addition to these long-term trends, there are also short-term challenges we must address together as an international community. These include climate change, pandemics, and cyber security threats. As we face these challenges, we must remember that our shared humanity transcends all boundaries of race, religion, or nationality.

In addition to economic growth, other trends are emerging in Asia that will further shape the future of the world economy:

Demographics: Asia is ageing rapidly, which means there will be fewer workers per capita in the coming decades and less consumption per capita. However, this demographic shift also allows businesses to meet these needs with products tailored to seniors’ markets or by creating social networks for them (e.g., Facebook).

Inflation is a risk, significantly if interest rates rise and economies slow. However, it is essential to realize that some of these fundamental demographic and economic forces have been reshaping Asia’s consumer market and these long-term forces are still at play today. Looking at the trendlines, not only headlines, is essential in these turbulent times.

However, it is essential to realize that some of these fundamental demographic and economic forces have been reshaping Asia’s consumer market and these long-term forces are still at play today. In these turbulent times, it

Asia’s middle class is reshaping the global economy.

Asia’s middle class is expanding at a rapid pace. The number of middle-class consumers in Asia might double by 2024, increasing their share of total wealth from one-third to 44% and their spending power by over $3 trillion.

The rise of the consumer class is a tectonic shift that started at the turn of the century. We can define three distinct periods of the height of the consumer class:

This decade will be South Asia’s turn, and we will see a substantial rise. There are 4 billion new consumers in the world.

The rise of the global middle class is one of the most important social transformations we have seen in our lifetime.

The emergence of a new consumer class is a crucial driver of economic growth, job creation, and innovation. It has been called “The greatest wealth creation opportunity since the Industrial Revolution” by McKinsey & Company, who forecasted that by 2030 there would be over 6 billion middle-class consumers globally — almost double today’s number — generating $86 trillion in annual consumption.

But it’s not just about numbers. For many people, becoming middle class means having their first car or home or smartphone Things that can transform their lives for good. In some countries, gaining access to electricity or clean drinking water can mean the difference between life and death for millions living in poverty. The rise of the global middle class means more freedom from hunger and disease, better education opportunities for children; improved health care services; more remarkable ability to save money and build assets; and more access to financial services such as loans and insurance products.

Leave a Reply